Overview

THE EARLY YEARS – THE ISSEI

Maple Leaf Grocery; Vancouver, BC; Institution: NNM;

Date: 1930;

Manzo Nagano, the first known immigrant from Japan, arrived in Canada in 1877. Like other minorities, Japanese Canadians had to struggle against prejudice and win a respected place in the Canadian mosaic through hard work and perseverance. Most of the issei (ees-say), first generation or immigrants, arrived during the first decade of the 20th century. They came from fishing villages and farms in Japan and settled in Vancouver, Victoria and in the surrounding towns. Others settled on farms in the Fraser Valley and in the fishing villages, mining, sawmill and pulp mill towns scattered along the Pacific coast. The first migrants were single males, but soon they were joined by young women and started families.

During this era, racism was a widely-accepted response to the unfamiliar, which justified the relegation of minorities to a lower status based on a purported moral inferiority. A strident anti-Asian element in BC society did its best to force the issei to leave Canada. In 1907, a white mob rampaged through the Chinese and Japanese sections of Vancouver to protest the presence of Asian workers who threatened their livelihood.They lobbied the federal government to stop immigration from Asia. The prejudices were also institutionalized into law. Asians were denied the vote; were excluded from most professions, the civil service and teaching; and were paid much less than their white counterparts.

Men working in the Maikawa Nippon Auto Supplies;

298 Alexander Street, Vancouver, BC

During the next four decades, BC politicians – with the exception of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) – catered to the white supremacists of the province and fueled the flames of racism to win elections.

To counteract the negative impacts of prejudice and their limited English ability, the Japanese, like many immigrants, lived in ghettos (the two main ones were Powell Street in Vancouver and the fishing village of Steveston) and developed their own institutions: schools, hospitals, temples, churches, unions, cooperatives and self- help groups. The issei’s contact with white society was primarily economic but the nisei (nee-say), second generation, were Canadian-born and were more attuned to life in the wider Canadian community. They were fluent in English, well-educated and ready to participate as equals but were faced with the same prejudices experienced by their parents. Their demand in 1936 for the franchise as Canadian-born people was denied because of opposition from politicians in British Columbia. They had to wait for another 13 years before they were given the right to vote.

THE WAR YEARS AND BEYOND-YEARS OF SORROW AND SHAME

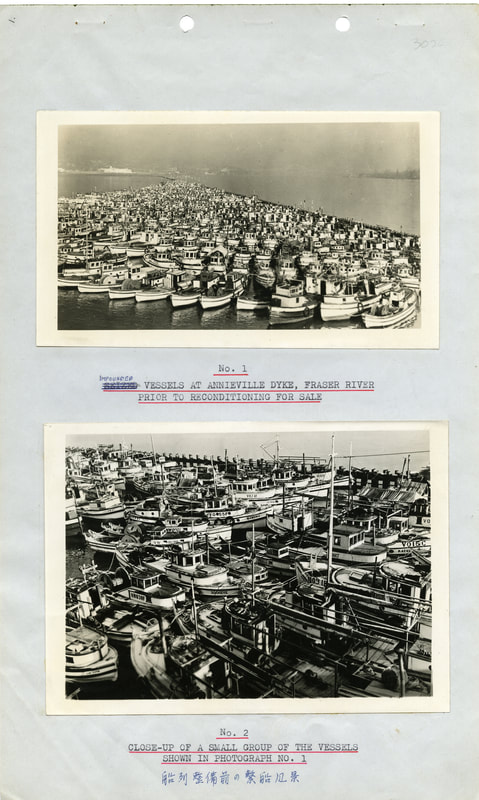

Impounded boats at Annieville dyke NNM 2010.4.2.1.001

Shortly after Japan’s entry into World War II on December 7, 1941, Japanese Canadians were removed from the West Coast. “Military necessity” was used as a justification for their mass removal and incarceration despite the fact that senior members of Canada’s military and the RCMP had opposed the action, arguing that Japanese Canadians posed no threat to security. And yet, the exclusion from the West Coast was to continue for four more years, until 1949. This massive injustice was a culmination of the movement to eliminate Asians from the West Coast begun decades earlier in British Columbia.

The order in 1942, to leave the “restricted area” and move 100 miles (160km) inland from the West Coast, was made under the authority of the War Measures Act. This order affected more than 21,000 Japanese Canadians. Many were first held in the livestock barns in Hastings Park (Vancouver’s Pacific National Exhibition grounds) and then were moved to hastily-built camps in the BC Interior. At first, many men were separated from their families and sent to road camps in Ontario and on the BC/Alberta border. Small towns in the BC Interior – such as Greenwood, Sandon, New Denver and Slocan – became internment quarters mainly for women, children and the aged. To stay together, some families agreed to work on sugar beet farms in Alberta and Manitoba, where there were labour shortages. Those who resisted and challenged the orders of the Canadian government were rounded up by the RCMP and incarcerated in a barbed-wire prisoner-of-war camp in Angler, Ontario.

Processing Japanese Canadians st the Socan City detention camp

Despite earlier government promises to the contrary, the “Custodian of Enemy Alien Property” sold the property confiscated from Japanese Canadians. The proceeds were used to pay auctioneers and realtors, and to cover storage and handling fees. The remainder paid for the small allowances given to those in internment camps. Unlike prisoners of war of enemy nations who were protected by the Geneva Convention, Japanese Canadians were forced to pay for their own internment. Their movements were restricted and their mail censored.

As World War II was drawing to a close, Japanese Canadians were strongly encouraged to prove their “loyalty to Canada” by “moving east of the Rockies” immediately, or sign papers agreeing to be “repatriated” to Japan when the war as over. Many moved to the Prairie provinces, others moved to Ontario and Quebec. About 4,000, half of them Canadian-born, one third of whom were dependent children under 16 years of age, were exiled in 1946 to Japan. Prime Minister Mackenzie King declared in the House of Commons on August 4, 1944: It is a fact that no person of Japanese race born in Canada has been charged with any act of sabotage or disloyalty during the years of war.

On April 1, 1949, four years after the war was over, all the restrictions were lifted and Japanese Canadians were given full citizenship rights, including the right to vote and the right to return to the West Coast. But there was no home to return to. The Japanese Canadian community in British Columbia was virtually destroyed.

1950s TO PRESENT - REBUILDING AND REVIVAL

Officer questioning Japanese-Canadian fishermen while confiscating their boat

Reconstructing lives was not easy, and for some it was too late. Elderly issei had lost everything they worked for all their lives and were too old to start anew. Many nisei had their education disrupted and could no longer afford to go to college or university. Many had to become breadwinners for their families. Property losses were compounded by long lasting psychological damage. Victimized, labeled “enemy aliens,” imprisoned, dispossessed and homeless, people lost their sense of self- esteem and pride in their heritage. Fear of resurgence of racial discrimination and the stoic attitude of “shikataga nai” (it can’t be helped) bred silence. The sansei (sun-say), third generation, grew up speaking English, but little or no Japanese. Today, most know little of their cultural heritage and their contact with other Japanese outside their immediate family is limited. The rate of intermarriage is very high – almost 90% according to the 1996 census.

With the changes to the immigration laws in 1967, the first new immigrants in 50 years arrived from Japan. The “shin” issei (“new” meaning the post WW II immigrant generation) came from Japan’s urban middle class. The culture they brought was different from the rural culture brought by the issei. Many of the cultural traditions – tea ceremony, ikebana, origami, odori (dance) – and the growing interest of the larger community in things Japanese such as the martial arts, revitalized the Japanese Canadian community. At the same time, gradual awareness of wartime injustices was emerging as sansei entered the professions and restrictions on access to government documents were lifted.

1980s – REDRESS MOVEMENT

The redress movement of the 1980s was the final phase within the Japanese Canadian community in the struggle for justice and recognition as full citizens of this country. In January 1984, the National Association of Japanese Canadians officially resolved to seek an acknowledgement of: the injustices endured during and after the Second World War; financial compensation for the injustices; and a review and amendment of the War Measures Act and relevant sections of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, so that no Canadian would ever again be subjected to such wrongs. With the formation of the National Coalition for Japanese Canadian Redress – which included representation from unions, churches, ethnic, multi-cultural and civil liberties groups – the community’s struggle became a Canadian movement for justice. They wrote letters of support and participated at rallies and meetings. A number of politicians also lent their support and advice.

The achievement of redress in September of 1988 is a prime example of a small minority’s struggle to overcome racism and to reaffirm the rights of all individuals in a democracy.

Japanese Canadian Redress Rally; Parliament Hill, Ottawa, ON

Prime Minister Brian Mulroney and Art Miki; Parliament Hill, Ottawa, ON

I know that I speak for Members on all sides of the House today in offering to Japanese Canadians the formal and sincere apology of this Parliament for those past injustices against them, against their families, and against their heritage, and our solemn commitment and undertaking to Canadians of every origin that such violations will never again in this country be countenanced or repeated. Prime Minister Brian Mulroney’s remarks to the House of Commons, Sept.22,1988