Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery

Morishta: A Portrait of the Morishta Family in their Living Room on Cordova Street; Vancouver, BC, 1939 [Many precious belongings, furniture, pianos, sewing machines, household goods and heirlooms were confiscated and auctioned off at bargain basment prices by the Canadian Government.

Morishta

Maikawa

Nakamura f

Maple Leaf Grocery

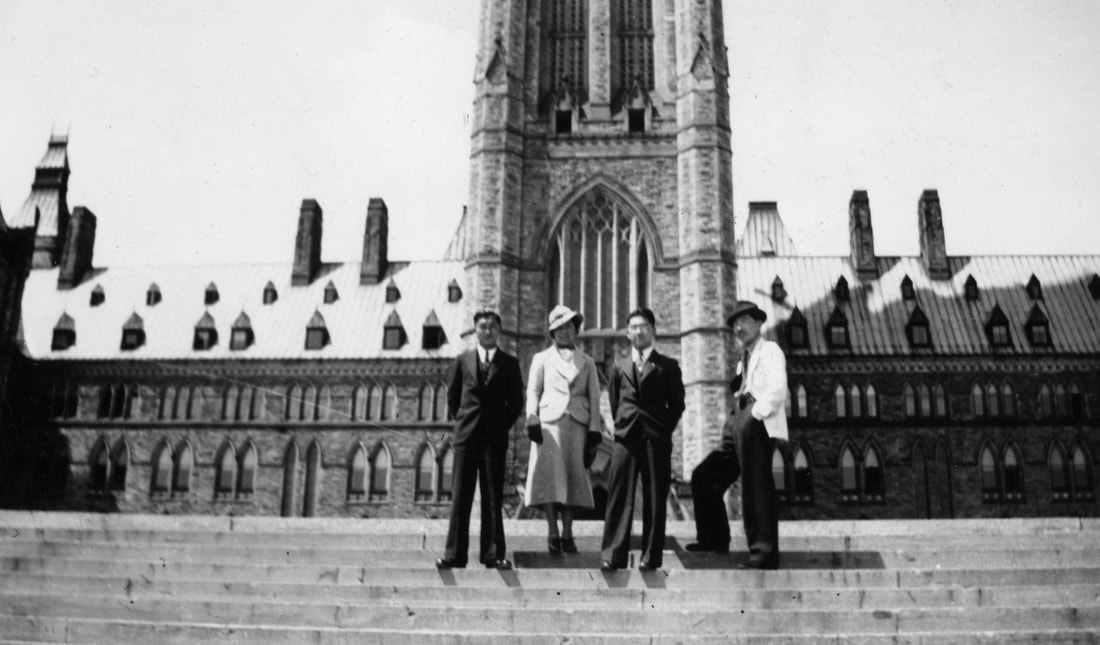

Delegation

Asahi

Mitsui

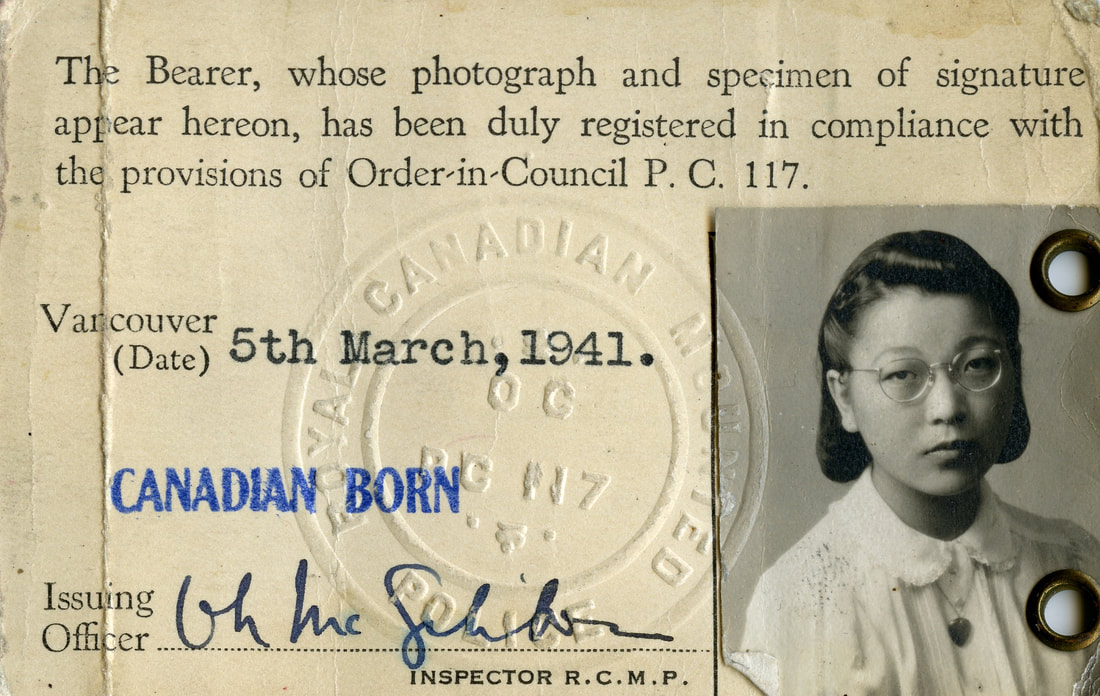

ID

RCMP

![Annieville: Fishing boats seized by the federal government in 1941. Within 48 hours of the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, some 1,200 fishing vessels owned by Japanese Canadians were seized and impounded. Japanese Canadian fishermen were stripped of their property, their independence, and their means of livelihood. They could not support their families. Many boats had their boats damaged and their gear stolen. [In January 1942, these boats, supposedly held in trust for interned Japanese Canadians, were sold to non-Japanese fisherman. The prices they received for their boats and gear were much less than the appraised value].](images/historical/annieville.jpeg)

Annieville

Cars

Walking

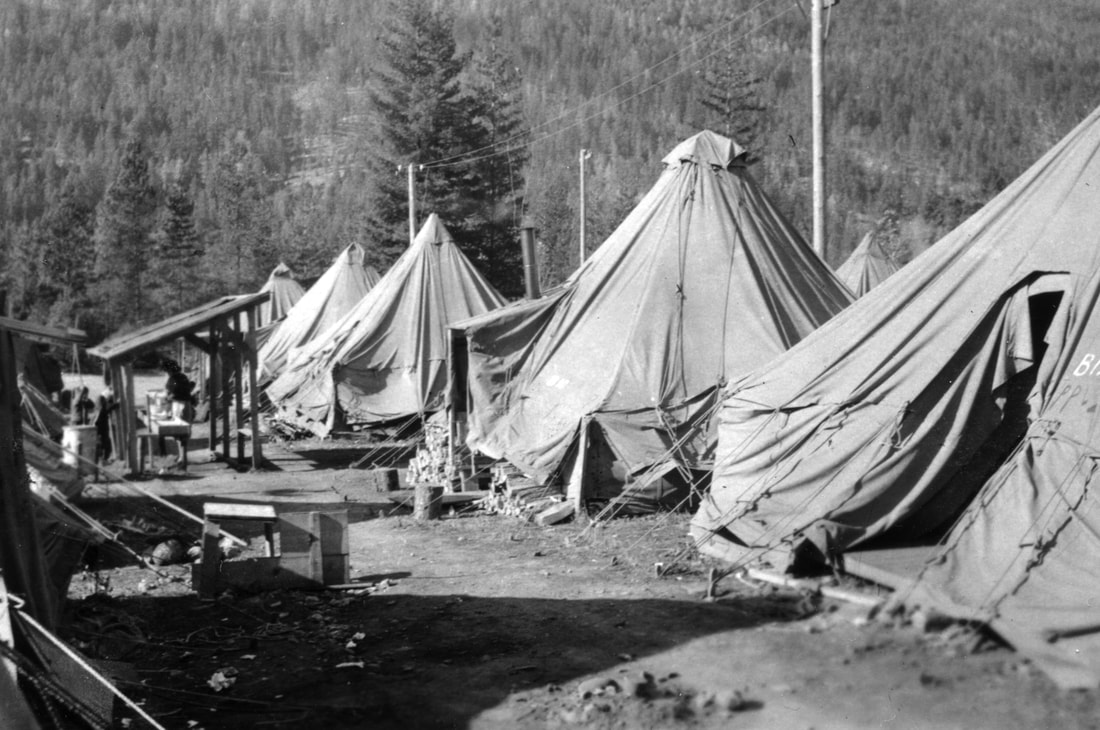

Straw

Forum

Livestock

Empty

Truck: Trucks and trains were used to ship Japanese Canadians to internment camps. The RCMP directed the loading. Women, children and the elderly were separated from their husbands and fathers who sere sent to work on road camps near the Rockies on the BC/Alberta border.

Truck

Slocan

Lemon Creek

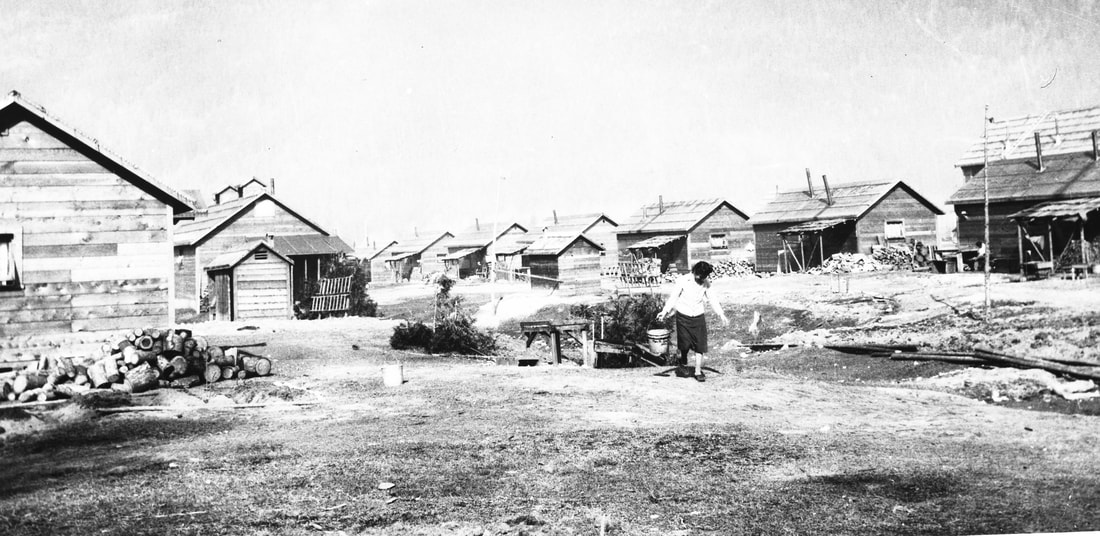

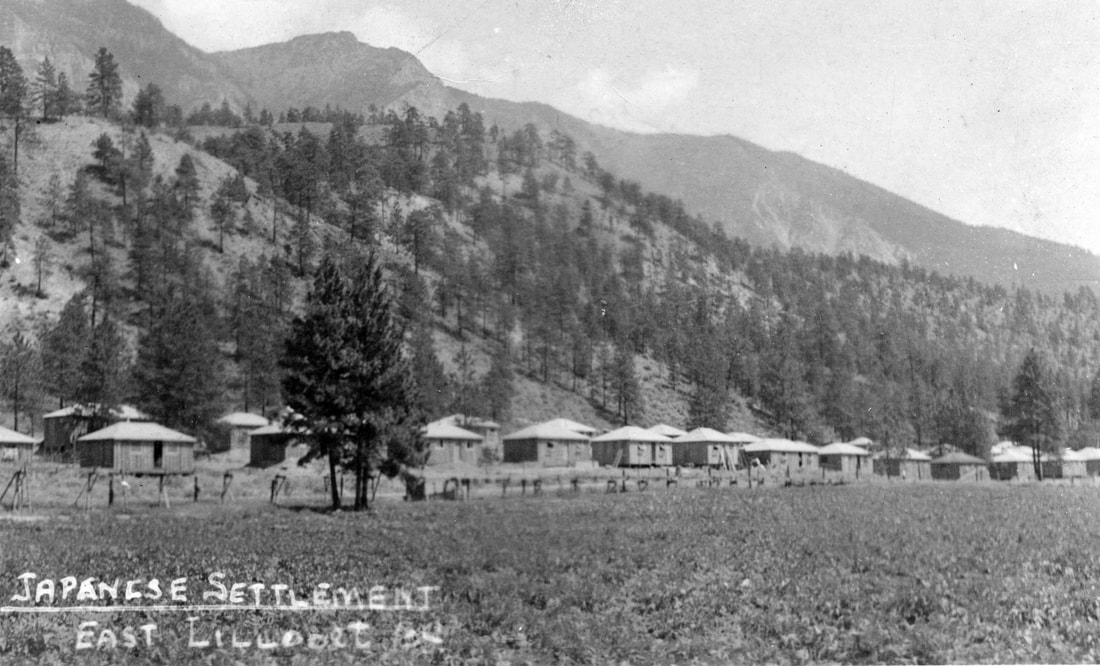

Japanese 'settlement'

Family in front of an internment shack.

Tashme, BC

?

Fumi Tamagi and three others picking Sugar Beets

Outdoor photography of the presentation of the 1944 May Queen and Court

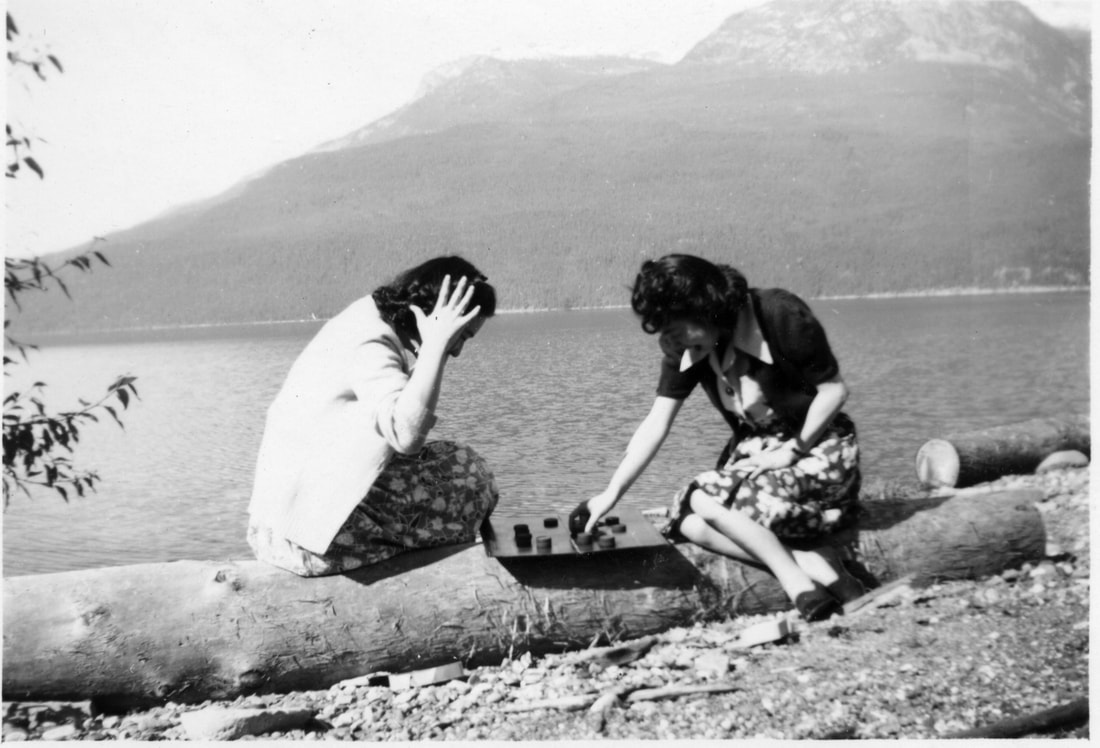

Two young women playing checkers at Slocan Lake.

Emi and Matsu Furakawa

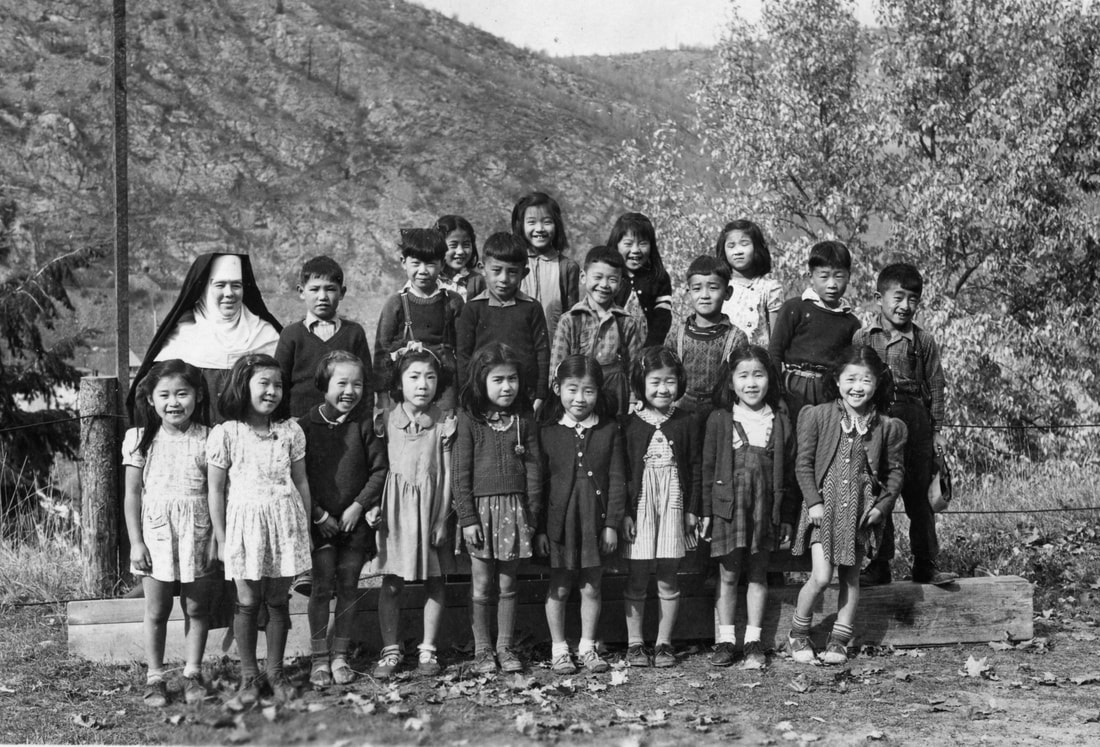

Nuns with children, 1944.

Burial of Masano Shirakawa

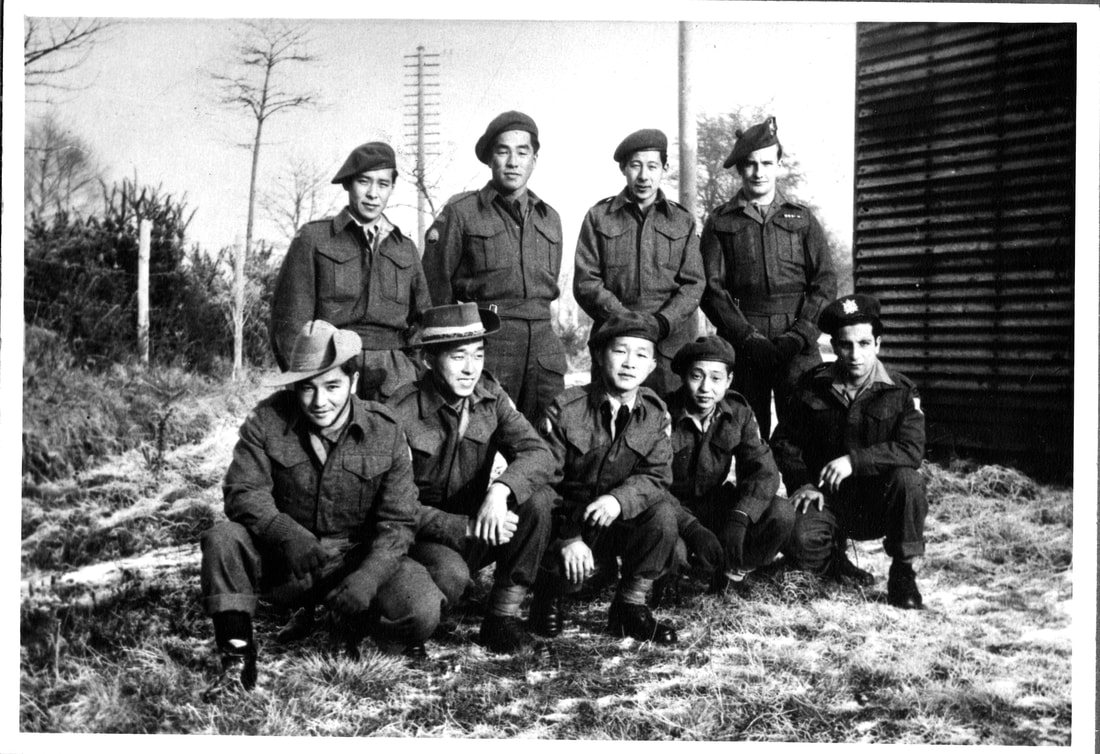

Canadian Nisei Veterans.

Redress

Redress